Do the hustle?

Is hustle culture the secret to success or the gateway to a toxic mindset?

What exactly is hustle culture?

Hustle culture is one of those terms that’s likely seeped into your consciousness even if you haven’t seen a definition for it. In short, it’s a workplace philosophy intensely focused on productivity, ambition, and success, with little regard for work-life balance.

Inspired by the culture at many Silicon Valley start-ups and egged on by any number of entrepreneurs lionized in the media, hustle culture sees life as a perpetual hamster wheel of striving. There’s always more money to be made, a career ladder to climb, or a more extraordinary achievement to be chased.

The high-profile success of technology titans like Google and Facebook led many to look to them as role models. And it wasn’t long before their all-consuming work cultures were credited as one of the secrets to their success. Some people began to believe that working extremely hard, only to push yourself even harder when you thought you’d already given your all, was a sign you were on your way to achieving greatness.

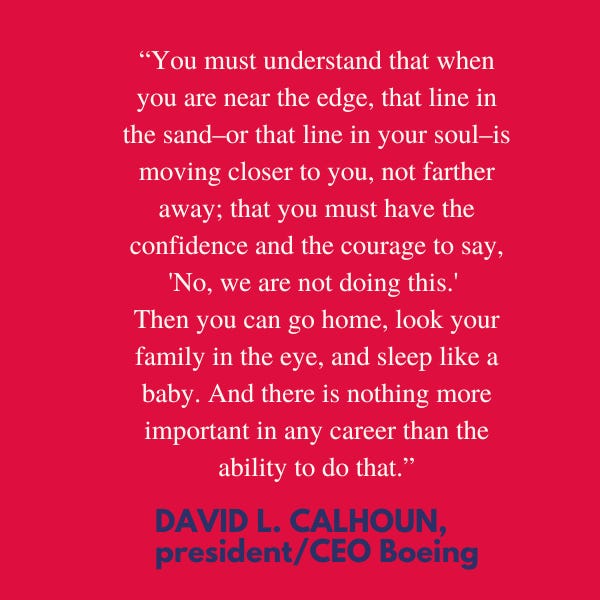

And with all those “rise and grind” social media posts from influencers and entrepreneurs, sometimes it seems like the only way to become successful and admired is by a ridiculous amount of hard work. As Elon Musk has proclaimed, “Nobody ever changed the world in 40 hours a week.”

Hustle culture isn’t new: A brief history of overworking in America

Though the term hustle culture was coined relatively recently, the concept isn’t new. Way back in 1607, when John Smith established the first permanent English settlement in America at Jamestown, one of the ways he ensured the colony survived was by enforcing the Puritan work ethic–reminding the ill-equipped settlers that he who did not work would not eat.

Over the next three centuries, the Puritan work ethic became enmeshed in American culture, aided by waves of immigration by Christian settlers who believed that excelling in work was a way to glorify God. Of course, back then, people essentially didn’t have a choice about how hard they worked–during the centuries before leisure time was invented, working long hours day after day was necessary for your family’s survival.

Though 70-hour 6-day workweeks were not uncommon at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, by the end of the 19th century, the workweek had shrunk to 60 hours. With the rise of the scientific management movement, businesses began studying how to increase worker productivity. They discovered that workers weren’t as productive after 8 hours.

In 1926, Henry Ford became one of the first business leaders to institute a 40-hour workweek after his own research showed that working longer yielded only a small increase in productivity. Although some companies followed his lead, it took the Great Depression, when a shorter workweek became a way to ease the massive unemployment crisis by spreading work hours across more people, to make it the norm.

In 1938, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, which required employers to pay overtime to employees working more than 44 hours a week. Two years later, the act was amended to make a 40-hour workweek the standard.

Despite these new norms, some salaried Americans were still tempted to work long hours to get ahead. And, of course, some employers encouraged this behavior by rewarding employees who came in early and stayed late with promotions and other perks. By the early 1970s, psychiatrist Wayne E. Oates coined the term “workaholics” to describe people for whom work could become an addiction akin to alcoholism.

So, the hustle culture is just the latest iteration of America's sometimes unholy Puritan work ethic.

Is work-life balance a better dance than the hustle?

You may be familiar with another catchphrase that’s become the holy grail for some people–work-life balance. (Maybe you heard your parents grumble this phrase under their breath as they tried to figure out how they would manage the demands of their jobs while also overseeing the care and feeding of you and your siblings, including shuttling you to all your extracurricular activities.)

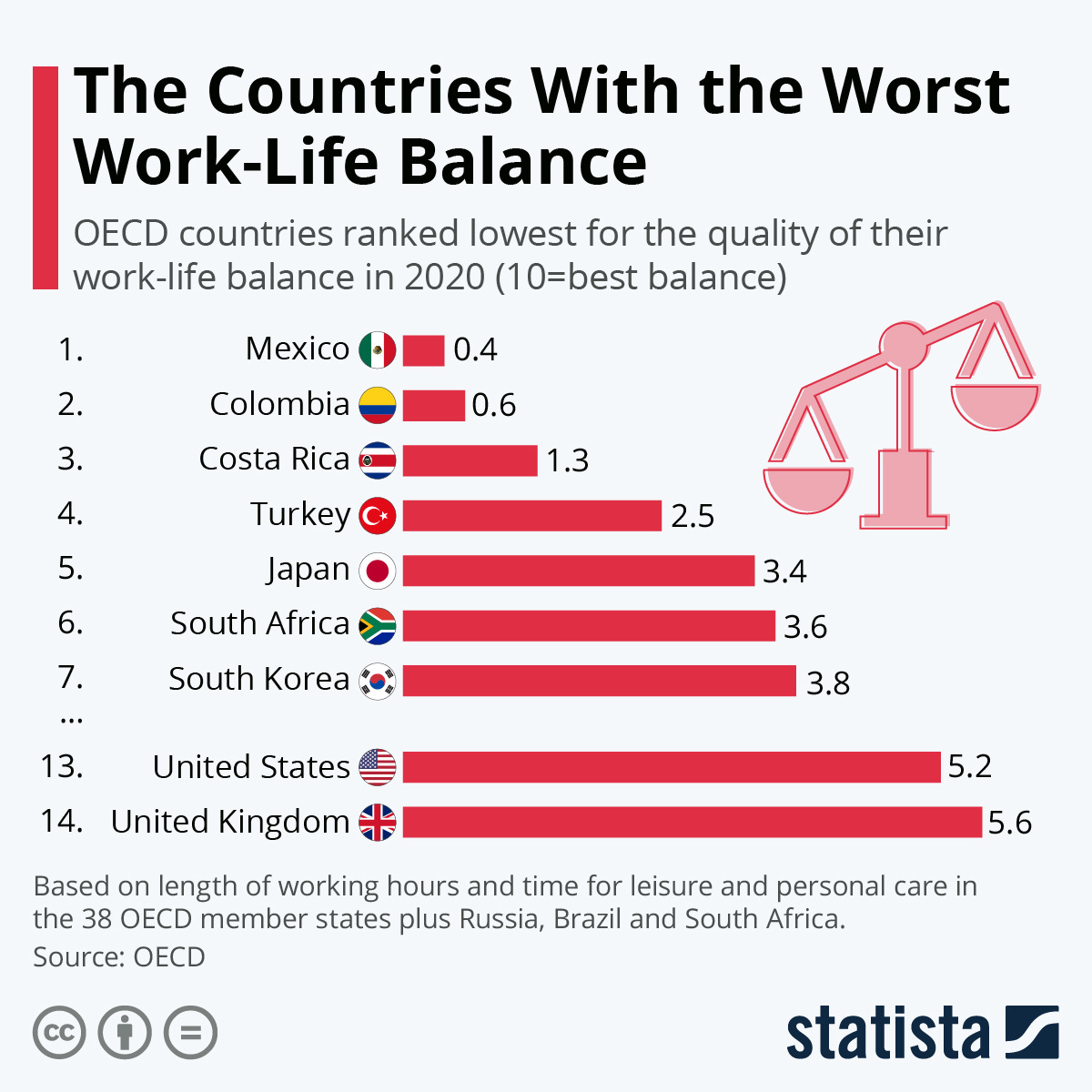

Though work-life balance has been an aspirational goal for many Americans since the 1980s, we struggle with achieving it. In 2020, the U.S. ranked as one of the countries having the worst work-life balance, coming in at #13.

The pandemic helped many Americans see that they had been packing 10 pounds into a 5-pound bag for too long. It’s no wonder that so many workers who found they were able to work quite well remotely have resisted the return to the office–people found that not having to run as hard on the hamster wheel felt a whole lot better.

Indeed, Pew Research reports that 71% of those who work from home all, most or some of the time, say doing so helps them balance their work and personal lives (52% say it helps a lot).

So, many people do find the work-life balance dance more enjoyable than the hustle.

What’s wrong with doing the hustle if you want to?

Some people hustle because they think doing more will lead to more money, greater prestige, and greater happiness. And sometimes it does, at least for a time. But it comes at a cost.

For one thing, it puts people at greater risk of anxiety. In hustle culture, too much is never enough–as soon as you’re close to achieving a goal, it seems like somebody moves the goalposts. It’s hard to live that way because you always have a sinking feeling that no matter how much you do, you’ll never be good enough.

Hustling can lead to stress and burnout, which appears pretty prevalent in many American workplaces:

According to the American Psychological Association’s 2021 Work and Wellbeing Survey, three out of five workers reported experiencing negative mental and physical impacts due to work-related stress. About 32% reported emotional exhaustion, and 44% noted high levels of physical fatigue.

An Indeed survey revealed that 52% of workers reported feeling burned out.

76% of respondents in a Mental Health America and FlexJobs study agreed that workplace stress affects their mental health and 75% experienced burnout.

Humans weren’t designed to work seven days a week. (If you think about it, even God took a day off while creating the world.) Though our 24/7 society has gotten to the point that taking one full day off once a week can seem like a radical idea, it wasn’t so long ago that many stores and businesses in America were closed on Sundays.

This past summer, PBS stations released the film SABBATH, in which documentary filmmaker Martin Doblmeier explored the religious, secular, psychological, and sociological implications of a weekly day of rest for a “profoundly burned-out world.” Who knows–maybe Americans are so tired that restoring a day of rest will catch on?

Whether or not the sabbath catches on again, there’s no getting around the fact that hustle culture brings another risk–future regrets. It’s been said that nobody on their deathbed wishes they spent more time at the office; most people say they wished they’d spent more time with their family.

I know it’s hard for people at the beginning of their careers to weigh whether this is so. But I will say that when I looked for photos of myself at work to help illustrate a talk I gave to students at my alma mater about my career, I didn’t have many pictures of myself at work. But I had albums full of photos of my family. (Finding photographs of my parents at work was a similar challenge when I was putting a commemorative book together for their 50th wedding anniversary.) I suspect that’s the case for most people.

What we preserve for posterity speaks volumes about what we truly value. So, you have to consider whether hustle culture aligns with this end goal.

Might you hustle for a while to prove you can?

Indeed, there are times in your career when you need to hustle. I still remember when one of our professors addressed all of us accounting majors on the subject of overtime just before interview season began: “Does anyone want to work a lot of overtime? Of course not. But if you don’t say you’ll be willing to work long hours when necessary, then you might as well bend over, put your head between your legs, and kiss your ass goodbye.”

Everyone has to demonstrate a willingness to go above and beyond for their job when necessary (and within reason), especially early in their careers. But what you might not recognize is that it’s easier than you might think to fall into a pattern of hustling beyond what is necessary and reasonable.

When I started working as a market research analyst for a pharmaceutical company, I felt like I had won the job lottery. I loved the projects I was working on, and the job came with opportunities to travel to numerous countries around the world to meet with our affiliates.

Until I joined my group, they hadn’t had a market researcher on the team, so I had all of the fun and some of the headaches that came with starting something from scratch. Of course, I wanted to do a great job. It was a fast-paced work environment, and some days, all it took was one fax to upend my work plan for the day. So, I started to take some folders home in my briefcase to tackle some of the projects that required deeper work that I didn’t have a chance to get to during my regular work hours.

It wasn’t like I was always working after hours, but for a time, it wasn’t unusual for me to work on things at home. It became almost like a hobby I turned to when I didn’t know what else to do with myself. After all, I’d spent so many years in college and grad school doing homework at night and on weekends. So, it was easy to fall into the habit of turning my job into something that required homework–even though my boss was not asking me to.

What saved me from succumbing to the fever of whatever we were calling hustle culture back then was the discovery that the summer interns hired from prestigious MBA programs were making more per hour than I was (a subject to delve into another day).

Though I couldn’t rectify that injustice immediately, it cured me of a desire to work more hours than were required. Why was I working unpaid overtime if I wasn’t compensated fairly during my regular hours? I realized that while I wanted to work to the best of my ability for my employer, my job wasn’t worthy of being enshrined on a pedestal that sat a little higher than everything else in my life.

Who knows–maybe I was ripe for this kind of epiphany because, with more work experience, I felt less of a need to prove myself to my coworkers and boss. In any case, I started to put a higher priority on work-life balance, and I was never sorry that I did.

Might you hustle now because it will be harder to do it later?

You probably already have a sneaky suspicion that eventually, if you become somebody’s parent, achieving work-life balance will become more challenging. And you’re right.

Pew Research has reported that parents of children under the age of 18 appear to have a harder time with the speed of modern life than those with older children or non-parents. A 2018 survey found that 74% of these parents said they at least sometimes felt too busy to enjoy life, compared with 55% of Americans with older children or no children at all. Parents of young children were also nearly twice as likely to say they felt this way all or most of the time (18% vs. 10%).

In a 2015 Pew Research survey, 31% of American parents with children under 18 said they always felt rushed. And while the overwhelming majority of parents found parenthood enjoyable (90%) and rewarding (88%) most or all of the time, sizable shares also found being a parent tiring (33%) and stressful (25%). Among parents with jobs, 56% said it was challenging to balance their work and family responsibilities.

If you are going to become somebody’s parent someday, it is true: You will never have as many hours to spend as you choose as you do before a baby arrives on the scene.

So sure, hustle while you can. But just be careful that you don’t get so good at the hustle that you don’t learn how to do the work-life balance dance. That’s a more complicated rhythm to pick up the longer you put off learning it.

Can you teach me how to do the hustle?

I was never that good at dancing the hustle. Though I kept working after my first child was born, and both my boss and my child seemed satisfied with my performance, I found it hard to keep up with having a full-time job, all of the household stuff, and having a baby.

By the late 90s, it seemed like many people in our situation—two college-educated parents with professional jobs and offspring—were figuring out how to keep all the plates spinning. But such a busy lifestyle made me feel harried a lot of the time. So when baby number two came along, I quit my job and consulted part-time instead. That’s another story for another day, but suffice it to say, I was unwilling to do the hustle for long.

However, there’s no shortage of people doing the hustle, so if you feel drawn to that dance, you won’t have to look very far to find a dance teacher.

But before you sign up for that kind of dance class, you might want to consider the motives of the people trying to entice you to hustle. David Heinemeier Hansson, co-founder of the software company Basecamp and author of the book It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work, has a theory that myths about overwork persist–despite data showing long hours improve neither productivity nor creativity–because they justify the extreme wealth created for a small group of elite techies. As Heinemeier Hansson told The New York Times, “The vast majority of people beating the drums of hustle-mania are not the people doing the actual work. They’re the managers, financiers, and owners.”

How to do the work-life balance dance

It isn’t the easiest dance to learn. But here are some basic principles to help you pick up its rhythm:

Be on guard for signs that you’re starting to do the hustle. Bragging about working all the time, sending emails and Slack messages at all hours of the day and night, ignoring personal commitments, and neglecting your personal life are all signs that you are dancing to the hustle culture’s tune. If you act like work is the most important thing in the world to you, it probably is—time to reevaluate whether your priorities are in order.

Don’t just define success in terms of money or professional achievements. Imagine your deathbed scene years from now–what experiences will you want to have had? How will you craft your lifestyle such that those things are possible?

When tempted to work late or longer, consider your motivation. Is this truly a special circumstance when working overtime is necessary, or are you just working because you don’t know what else to do with yourself? If it’s the latter, ask yourself if you are avoiding someone or something by working long hours. If that’s not the issue, perhaps you should become more intentional about adding other things into the mix of your life (hobbies, relationships, rest, etc.).

Set boundaries. It may be tempting to earn some brownie points by responding to Slack or email on the weekends to create the perception that you’re always on the job, but consider what message that sends to your boss. Do you really want to be considered available outside of regular working hours?

Don’t consider rest and recreation optional. Consider sleeping 7-8 hours a night standard and try to make leisurely pursuits of one kind or another a priority at least one day of the weekend. Remember that taking a break from work is part of what helps to restore your mind and body so that you’re ready to give your all during the work week. I’ll bet that, just like Henry Ford discovered a century ago, it will help make you more productive.

The next entry from the Books of Wisdom collection is going to cover us for two months. With no issues coming during the weeks of Thanksgiving and Christmas (striving to be a good example of work-life balance haha), The Best Advice I Ever Got will be in the spotlight for both November and December.

Katie Couric, journalist and former anchor of the CBS Evening News, asked the many remarkable people she'd interviewed over the years to share lessons from their lives. The result was The Best Advice I Ever Got.

Couric notes, “I've always found comfort and guidance in hearing from people who have wrestled with the same questions and, through the simple act of living, have found their own versions of the right answers.

“These stories aren't just for those who are starting out; they're for those who are starting over, or just taking stock--a reminder of what is important and how we can better live our lives every day.”

Stay tuned for more samples from The Best Advice I Ever Got next week.

In the olden days, moms used to clip articles from newspapers for their kids if they thought it was something they needed to know. I’ll be keeping an eye out for things that you might have missed that may be helpful to you.

This week’s clips:

The New Yorker considers why requiring rest rather than work is still a radical idea.

For all those celebrating Taylor’s release of her version of 1989: musings in America Magazine on how Taylor reckons with her past self.

Next Week: Signs you may have met your lobster How to know when he's/she's the one